The rise and fall of America’s biggest conversion ministry reveal some ugly, unholy truths

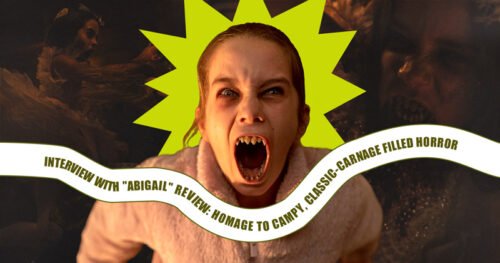

Jeffrey McCall is on the road, bringing with him a poster sign that says “TRANS 2 CHRIST” in gold glitter. He pulls up to a building, and he paces outside; upon seeing a group of women exit, he intercepts. “Do y’all need any prayer tonight?” he asks. “I’m just out here praying for people.” On top of sharing prayer with these strangers, he bears a testimony: he once lived as a transgender woman and left everything to follow Jesus.

A believer not only in Christ but the power of LGBTQ conversion, McCall here is just one of many using his story to prove that queer people can—and should—change. Conversion therapy ministries have sprung from this one belief. And there are those that continue on today, despite major medical and mental health associations firmly establishing their practices as harmful.

This is what the Netflix documentary Pray Away rips into, taking aim at a famous American megachurch that, for three decades, dedicated itself to the “ex-gay” movement.

Directed by Kristine Stolakis and executively produced by Ryan Murphy and Jason Blum, Pray Away need not come with a trigger warning to convey that an uncomfortable confrontation lies ahead. For members of the LGBTQ, a level of emotional preparedness is necessary, but perhaps not for the kind of jolt one might expect. This is a controversial issue where lives are at stake. But while the film tackles that head-on, it doesn’t charge ahead like a bull in a china shop in order to drive home what viewers ought to already know: conversion therapy is wrong and it needs to end. Instead, Pray Away delicately approaches that same conclusion by using Exodus as a gleaming use case.

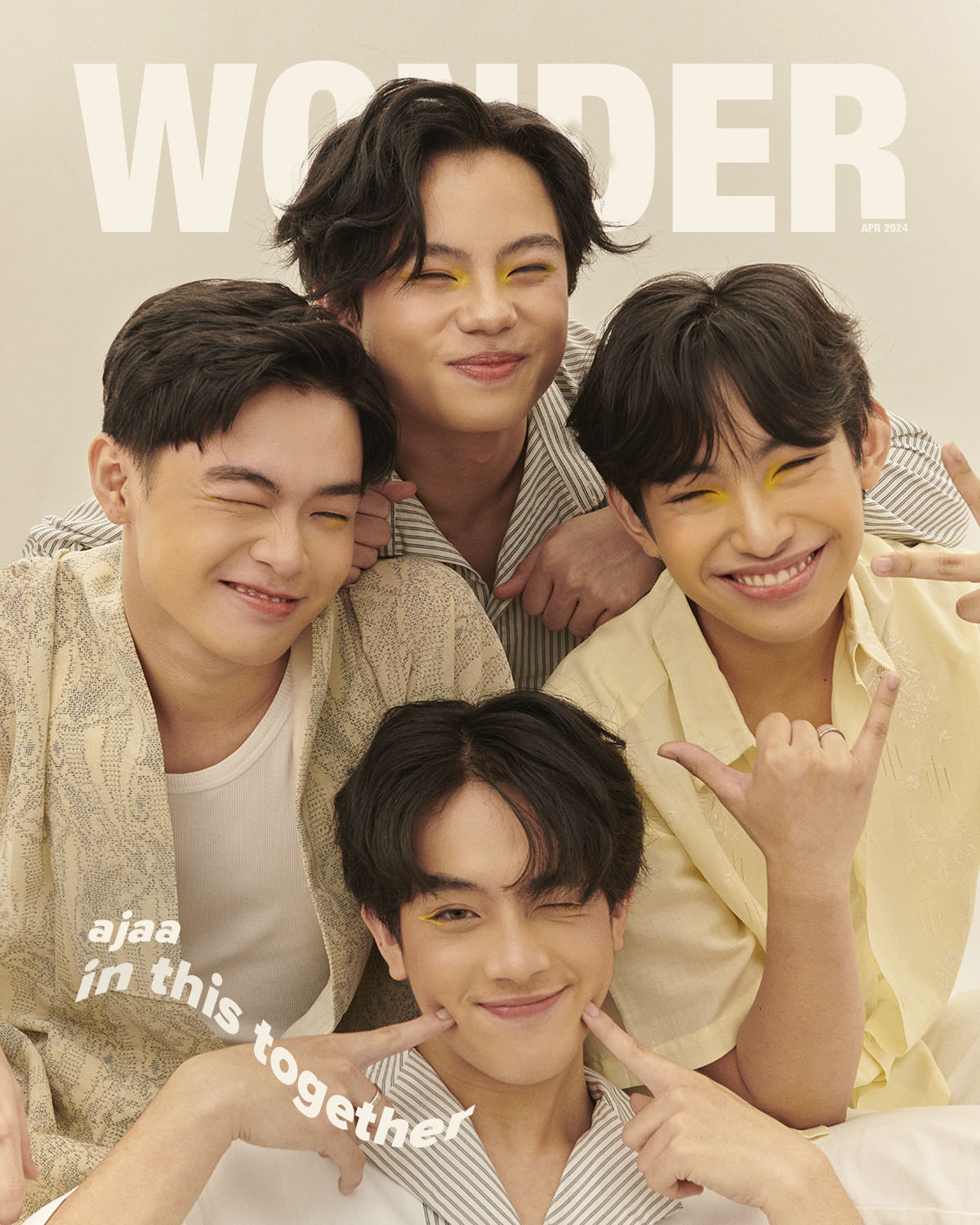

Congregation praying during the testimony of Jeffrey McCall, founder of Freedom March, a millennial-driven “ex-gay” organization. Photo: Multitude Films

RELATED: “Allyship Is a Verb” and Other Lessons on Becoming an LGBTQIA+ Ally

Pray Away is no light watch given the breadth of what it addresses alone. It’s an ambitious feat to recount the rise and fall of a megachurch, to adequately answer the how’s and why’s and still leave viewers feeling moved, feeling the weight but not weighed down. Even with a running time of one hour and 41 minutes, it paces itself nicely. It’s successful at revealing the dangers of the systematic (“systematic” being the operative word, really) attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. The manner in which the film does this is notable, too, since it highlights the individual just as much, if not, more often.

This documentary brings together four Exodus ex-leaders, who speak on their personal experiences: from a single soul merely wanting to belong somewhere, anywhere, to ultimately becoming the poster child or mouthpiece of the movement (one that unfortunately made away with that soul). Each one of these ex-leaders today has come back out as a member of the LGBTQ, they themselves denouncing the practice they once actively took part in.

Conversion therapy survivor Julie Rodgers at church. Photo: Multitude Films

Through conversion therapy ministries like Exodus, the act of leaving or walking away from the “homosexual lifestyle” is made simple and inviting. One Christian quips that she spent six years as a “practicing lesbian” before she found Jesus. This story fast-forwards to the woman already “cured” since heeding a call plastered across TV screens and spread through word of mouth, conservative community to conservative community: “Unhappy and gay? Join the Exodus.”

Such was the case for the four ex-Exodus leaders, too, who were conditioned, from the jump, to believe that unhappiness and homosexuality were inextricably linked. Wanting to be happy meant needing to be cured. Exodus peddled itself not only as the antidote, but a structure that provided clarity, care and guidance, and a new circle of people like them, already saved or about to be saved.

RELATED: Let’s Talk About Mental Health: How to Be an Ally to the LGBTQIA+ Community

Exodus, like many of the megachurches, thrived in operating in this kind of bubble. In watching the archival footage of sessions like bible study, behavior modification and peer counseling, Pray Away becomes its most uncomfortable and, frankly, most angering. Exodus counselors with no qualifications to hold such activities were the judge and jury. They went by their unfounded beliefs to try and rewire the individual. This meant linking vice and sin and lack with homosexuality. The matter-of-fact delivery of this untruth could easily leave anyone squeamish.

“They were in no way equipped to deal with the reactions,” one of the ex-leaders shared, pointing out that many participants experienced depression, dealt with panic attacks or attempted suicide because they felt they weren’t changing under the program. “We really believe that if you kept repeating it, if you kept claiming that god was changing you, that he would.”

Still, the successes of Exodus kept coming, earning the community political clout and soon revealing the politics of religion. As Pray Away continues to document the group’s steady rise well into the 2000s, it uncovers the many other tentacles latched onto the movement: Exodus-employed psychologists who made a living out of pseudo-psychology to legitimize conversion therapy. The advances of equal rights as an affront to Christian values. Self-acceptance, body autonomy and independent thought as “part of the secular agenda. The oppression of women through and through, where they were made to subscribe to antiquated norms because “the feminine is something God loves,” makeup lessons included.

RELATED: Love, Light, Family: Stories of Coming Out Featuring Parents of the LGBTQ+

The domino effect of destruction that comes after is a tear-jerking manifesto: that one cannot pray the gay away, but the attempt alone can cripple. In the film’s most powerful moment, survivors of the practice share how the wounds of conversion therapy cut deep and endure. “Shortly after I came out, a gay person said very bluntly and directly that I had blood on my hands,” shares one ex-leader. “He said, ‘What do you think about the blood on your hands?’ I said, ‘Right now, all I know is I’m afraid to look down at my hands.’”

Prayer gathering of Freedom March members, a millennial-driven “ex-gay” organization. Photo: Multitude Films

With this groundbreaking account, Pray Away hopes to hammer down the final nail on the coffin of the now widely-denounced practice. Yet its ending hardly feels triumphant. As one church shuts down, the film reminds, many others prop up.

Exodus International, the largest and oldest megachurch, closed its doors in 2013, but the pangs of justice are not felt. There are no winners and losers here. Only survivors. Survivors learning to reckon with the wrong they’ve done to others or the wrong done unto them, only hoping nobody else has to endure it.

RELATED: How You Can Put LGBTQIA+ Safe Spaces on the Map

If you or someone you know is struggling, visit wannatalkaboutit.com for information on how to find support. In the Philippines, you can get in touch with the 24/7 help hotline HOPELINE through (0918) 873 4673, (02) 8 804 4673, (0917) 558 4673.

Art Alexandra Lara